Abstract rewriting system

In mathematical logic and theoretical computer science, an abstract rewriting system (also (abstract) reduction system or abstract rewrite system; abbreviation ARS) is a formalism that captures the quintessential notion and properties of rewriting systems. In its simplest form, an ARS is simply a set (of "objects") together with a binary relation, traditionally denoted with  ; this definition can be further refined if we index (label) subsets of the binary relation. Despite its simplicity, an ARS is sufficient to describe important properties of rewriting systems like normal forms, termination, and various notions of confluence.

; this definition can be further refined if we index (label) subsets of the binary relation. Despite its simplicity, an ARS is sufficient to describe important properties of rewriting systems like normal forms, termination, and various notions of confluence.

Historically, there have been several formalizations of rewriting in an abstract setting, each with its idiosyncrasies. This is due in part to the fact that some notions are equivalent, as we shall see in this article. The formalization that is most commonly encountered in monographs and textbooks, and which we generally follow here, is due to Gérard Huet (1980).[1]

Contents |

Definition

We need to specify a set of objects and the rules that can be applied to transform them. The most general (unidimensional) setting of this notion is called an abstract reduction system, (abbreviated ARS), although more recently authors use abstract rewriting system as well.[2] (The preference for the word "reduction" here instead of "rewriting" constitutes a departure from the uniform use of "rewriting" in the names of systems that are particularizations of ARS. Because the word "reduction" does not appear in the names of more specialized systems, in older texts reduction system is a synonym for ARS).[3]

An ARS is simply a set A, whose elements are usually called objects, together with a binary relation on A, traditionally denoted by →, and called the reduction relation, rewrite relation[4] or just reduction.[5] This (entrenched) terminology using "reduction" is a little misleading, because the relation is not necessarily reducing some measure of the objects; this will become more apparent when we discuss string rewriting systems further in this article.

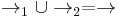

In some contexts it may be beneficial to distinguish between some subsets of the rules, i.e. some subsets of the reduction relation →, e.g. the entire reduction relation may consist of associativity and commutativity rules. Consequently, some authors define the reduction relation → as the indexed union of some relations; for instance if  , the notation used is (A, →1, →2).

, the notation used is (A, →1, →2).

As a mathematical object, an ARS is exactly the same as unlabeled state transition system, and if we consider the relation as an indexed union, then an ARS is the same as a labeled state transition system with the indices being the labels. The focus of the study, and the terminology are different however. In a state transition system one is interested in interpreting the labels as actions, whereas in an ARS the focus is on how objects may be transformed (rewritten) into others.[6]

Example 1

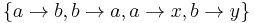

Suppose the set of objects is T = {a, b, c} and the binary relation is given by the rules a → b, b → a, a → c, and b → c. Observe that these rules can be applied to both a and b in any fashion to get c. Such a property is clearly an important one. Note also, that c is, in a sense, a "simplest" object in the system, since nothing can be applied to c to transform it any further.

Basic notions

Example 1 leads us to define some important notions in the general setting of an ARS. First we need some basic notions and notations.[7]

is the transitive closure of

is the transitive closure of  , where = is the identity relation, i.e.

, where = is the identity relation, i.e.  is the smallest preorder (reflexive and transitive relation) containing

is the smallest preorder (reflexive and transitive relation) containing  . It is also called the reflexive transitive closure of

. It is also called the reflexive transitive closure of  .

. is

is  , that is the union of the relation → with its inverse relation, also known as the symmetric closure of

, that is the union of the relation → with its inverse relation, also known as the symmetric closure of  .

. is the transitive closure of

is the transitive closure of  , that is

, that is  is the smallest equivalence relation containing

is the smallest equivalence relation containing  . It is also known as the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of

. It is also known as the reflexive transitive symmetric closure of  .

.

Normal forms and the word problem

An object x in A is called reducible if there exist some other y in A and  ; otherwise it is called irreducible or a normal form. An object y is called a normal form of x if

; otherwise it is called irreducible or a normal form. An object y is called a normal form of x if  , and y is irreducible. If x has a unique normal form, then this is usually denoted with

, and y is irreducible. If x has a unique normal form, then this is usually denoted with  . In example 1 above, c is a normal form, and

. In example 1 above, c is a normal form, and  . If every object has at least one normal form, the ARS is called normalizing.

. If every object has at least one normal form, the ARS is called normalizing.

One of the important problems that may be formulated in an ARS is the word problem: given x and y are they equivalent under  ? This is a very general setting for formulating the word problem for the presentation of an algebraic structure. For instance, the word problem for groups is a particular case of an ARS word problem. Central to an "easy" solution for the word problem is the existence of unique normal forms: in this case if two objects have the same normal form, then they are equivalent under

? This is a very general setting for formulating the word problem for the presentation of an algebraic structure. For instance, the word problem for groups is a particular case of an ARS word problem. Central to an "easy" solution for the word problem is the existence of unique normal forms: in this case if two objects have the same normal form, then they are equivalent under  . The word problem for an ARS is undecidable in general.

. The word problem for an ARS is undecidable in general.

Joinability and the Church–Rosser property

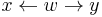

A related, but weaker notion than the existence of normal forms is that of two objects being joinable: x and y are said joinable if the exists some z with the property that  . From this definition, it's apparent one may define the joinability relation as

. From this definition, it's apparent one may define the joinability relation as  , where

, where  is the composition of relations. Joinability is usually denoted, somewhat confusingly, also with

is the composition of relations. Joinability is usually denoted, somewhat confusingly, also with  , but in this notation the down arrow is a binary relation, i.e. we write

, but in this notation the down arrow is a binary relation, i.e. we write  if x and y are joinable.

if x and y are joinable.

An ARS is said to possess the Church-Rosser property if and only if  implies

implies  for all objects x, y. Equivalently, the Church-Rosser property means that the reflexive transitive symmetric closure is contained in the joinability relation. Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser proved in 1936 that lambda calculus has this property;[8] hence the name of the property.[9] (The fact that lambda calculus has this property is also known as the Church-Rosser theorem.) In an ARS with the Church-Rosser property the word problem may be reduced to the search for a common successor. In a Church-Rosser system, an object has at most one normal form; that is the normal form of an object is unique if it exists, but it may well not exist. In lambda calculus for instance, the expression (λx.xx)(λx.xx) does not have a normal form because there exists an infinite sequence of beta reductions (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → ...[10]

for all objects x, y. Equivalently, the Church-Rosser property means that the reflexive transitive symmetric closure is contained in the joinability relation. Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser proved in 1936 that lambda calculus has this property;[8] hence the name of the property.[9] (The fact that lambda calculus has this property is also known as the Church-Rosser theorem.) In an ARS with the Church-Rosser property the word problem may be reduced to the search for a common successor. In a Church-Rosser system, an object has at most one normal form; that is the normal form of an object is unique if it exists, but it may well not exist. In lambda calculus for instance, the expression (λx.xx)(λx.xx) does not have a normal form because there exists an infinite sequence of beta reductions (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → (λx.xx)(λx.xx) → ...[10]

Notions of confluence

Various properties, simpler than Church-Rosser, are equivalent to it. The existence of these equivalent properties allows one to prove that a system is Church-Rosser with less work. Furthermore, the notions of confluence can be defined as properties of a particular object, something that's not possible for Church-Rosser. An ARS  is said to be,

is said to be,

- confluent if and only if for all w, x, and y in A,

implies

implies  . Roughly speaking, confluence says that no matter how two paths diverge from a common ancestor (w), the paths are joining at some common successor. This notion may be refined as property of a particular object w, and the system called confluent if all its elements are confluent.

. Roughly speaking, confluence says that no matter how two paths diverge from a common ancestor (w), the paths are joining at some common successor. This notion may be refined as property of a particular object w, and the system called confluent if all its elements are confluent. - semi-confluent if and only if for all w, x, and y in A,

implies

implies  . This differs from confluence by the single step reduction from w to x.

. This differs from confluence by the single step reduction from w to x. - locally confluent if and only if for all w, x, and y in A,

implies

implies  . This property is sometimes called weak confluence.

. This property is sometimes called weak confluence.

Theorem. For an ARS the following three conditions are equivalent: (i) it has the Church-Rosser property, (ii) it is confluent, (iii) it is semi-confluent.[11]

Corollary.[12] In a confluent ARS if  then

then

- If both x and y are normal forms, then x = y.

- If y is a normal form, then

Because of these equivalences, a fair bit of variation in definitions is encountered in the literature. For instance, in Terese the Church-Rosser property and confluence are defined to be synonymous and identical to the definition of confluence presented here; Church-Rosser as defined here remains unnamed, but is given as an equivalent property; this departure from other texts is deliberate.[13] Because of the above corollary, one may define a normal form y of x as an irreducible y with the property that  . This definition, found in Book and Otto, is equivalent to common one given here in a confluent system, but it is more inclusive in a non-confluent ARS.

. This definition, found in Book and Otto, is equivalent to common one given here in a confluent system, but it is more inclusive in a non-confluent ARS.

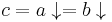

Local confluence on the other hand is not equivalent with the other notions of confluence given in this section, but it is strictly weaker than confluence. The typical counterexample is  , which is locally confluent but not confluent.

, which is locally confluent but not confluent.

Termination and convergence

An abstract rewriting system is said to be terminating or noetherian if there is no infinite chain  . In a terminating ARS, every object has at least one normal form, thus it is normalizing. The converse is not true. In example 1 for instance, there is an infinite rewriting chain, namely

. In a terminating ARS, every object has at least one normal form, thus it is normalizing. The converse is not true. In example 1 for instance, there is an infinite rewriting chain, namely  , even though the system is normalizing. A confluent and terminating ARS is called convergent. In a convergent ARS, every object has a unique normal form. But it is sufficient for the system to be confluent and normalizing for a unique normal to exist for every element, as seen in example 1.

, even though the system is normalizing. A confluent and terminating ARS is called convergent. In a convergent ARS, every object has a unique normal form. But it is sufficient for the system to be confluent and normalizing for a unique normal to exist for every element, as seen in example 1.

Theorem (Newman's Lemma): A terminating ARS is confluent if and only if it is locally confluent.

The original 1942 proof of this result by Newman was rather complicated. It wasn't until 1980 that Huet published a much simpler proof exploiting the fact that when  is terminating we can apply well-founded induction.[14]

is terminating we can apply well-founded induction.[14]

Notes

- ^ Book and Otto, p. 9

- ^ Terese, p. 7,

- ^ Book and Otto, p. 10

- ^ Terese, p. 7

- ^ Book and Otto, p. 10

- ^ Terese, p. 7-8

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, pp. 8-9

- ^ Alonzo Church and J. Barkley Rosser. Some properties of conversion. Trans. AMS, 39:472-482, 1936

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 9

- ^ S.B. Cooper, Computability theory, p. 184

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 11

- ^ Baader and Nipkow, p. 12

- ^ Terese p.11

- ^ Harrison, p. 260

Further reading

- Baader, Franz; Nipkow, Tobias (1998). Term Rewriting and All That. Cambridge University Press. A textbook suitable for undergraduates.

- Nachum Dershowitz and Jean-Pierre Jouannaud Rewrite Systems, Chapter 6 in Jan van Leeuwen (Ed.), Handbook of Theoretical Computer Science, Volume B: Formal Models and Sematics., Elsevier and MIT Press, 1990, ISBN 0-444-88074-7, pp. 243–320. The preprint of this chapter is freely available from the authors, but it misses the figures.

- Ronald V. Book and Friedrich Otto, String-rewriting Systems, Springer (1993). Chapter 1, "Abstract reduction systems"

- Marc Bezem, Jan Willem Klop, Roel de Vrijer ("Terese"), Term rewriting systems, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-39115-6, Chapter 1. This is a comprehensive monograph. It uses however a fair deal of notations and definitions not commonly encountered elsewhere. For instance the Church–Rosser property is defined to be identical with confluence.

- John Harrison, Handbook of Practical Logic and Automated Reasoning, Cambridge University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-89957-4, chapter 4 "Equality". Abstract rewriting from the practical perspective of solving problems in equational logic.

- Gérard Huet, Confluent Reductions: Abstract Properties and Applications to Term Rewriting Systems, Journal of the ACM (JACM), October 1980, Volume 27, Issue 4, pp. 797–821. Huet's paper established many of the modern concepts, results and notations.